Home ✧ About ✧ Sitemap ✧ Neighbors ✧ Guestbook

Ladder to the Moon ; 1958 AD ; Abiquiú, United States of America ; 40 x 30 in ; Oil on linen

I’m so intrigued by this. I love that the ladder is hanging in mid-air, not quite a ladder to the sky as much as a ladder in the sky. There’s a moon far above it, and land far below, but it can’t quite reach either; there’s no real beginning or destination to the journey it provides. Is the effort fruitless? Is that devastating or liberating?

It also makes me think about the way we approach life. If we think of our world as a march from life ‘til death… I don’t know. Maybe for some people, it’s empowering, but it doesn’t feel that way to me. We need to find importance in simply existing– not just in getting somewhere.

The colors aren’t exactly muted, but they’re soft and comforting. It feels like a dream, and also sort of reminds me of Salvador Dali (booo). I love how green and lush the mountains below are, and that the moon is only a half moon (opposition, two sides to something bigger, divinity, cycles, etc). Is this meant to be a link between nature and the cosmos? Humankind and the universe around us? Also, I can’t tell if this is just an issue of image quality, but it looks almost as if the color between the rungs of the ladder is lighter and more turquoise-y than most of the sky. It’s like it’s a different realm entirely, climbing along and experiencing that journey.

The ladder to me is just another place. It’s not just a transitive space, meant to get you from one to another, but its own world/realm. I think a lot of people would think almost instantly that we humans are beginning on Earth, because that’s what’s familiar to us. What if we started on the ladder? Or on the moon? I’m not sure.

Journey of the Wounded Healer ; 1985 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 216 x 90 in ; Oil on linen

I’m sort of awestruck. There’s so much going on here– a lot of imagery both traditional and entirely reimagined. It’s a triptych that seems to have some sort of progression or narrative, though I can’t tell quite how. I’m just going to walk through them so I can find the story as I go.

In the first, a skinless/muscle-less skeleton (though it has a sort of green aura that seems to emulate the skin’ seems to be diving head first through space, wrapped in a spiraling DNA double helix. It has a hand on its head, signaling frustration or exhaustion of some kind– like it’s really getting to the end of its rope.

In the second, it’s exploding (though it doesn’t seem like it’s entirely the same creature, as it has skin and muscle and stuff). It’s being torn apart, seemingly as if because of a pressure build up. Honestly, it looks really painful. But also expansive and freeing? I see a lot of serpent symbolism which is intriguing… represents healing, rebirth, transformation, etc.

We see that especially in the last one, where the man is climbing upward, with a sort of heavenly glow/aura around him and holding the caduceus. I can’t tell if it was meant to be the Rod of Asclepius (often mistaken) for medical purposes, or is meant to be Hermes’ staff (rebirth symbolism, likely), but both definitely work. There’s awakening, ascendence, and more.

I can also read this as not quite narrative but simultaneous– maybe instead, it’s meant to be mind, body, and spirit all at once. An opening up and understanding– painful and incredible.

It’s such a weird piece. Very, very cool.

Lisa Lyon ; 1980-1982 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 101 x 75.6 cm ; Photograph, gelatin silver print

I love this. I can’t tell what’s going on with the sort of plate she’s leaning against, but we see a woman in a very old-fashioned hat (with white flowers– very feminine & soft) and veil, both black. It feels sort of like mourning attire, but then she wears an incredibly tight, low-cut, and sort of sexy leather dress/top. All the while, she has one arm flexed and is holding her wrist as she clenches her fist. There’s masculinity and femininity intertwined.

There’s so much juxtaposition in this piece, especially enhanced by the black and white lighting. It’s very intense and weird to me, and I like it a lot. She’s defined, and so is everything.

I think there’s an interesting exploration about grief, mourning, and strength, but also about different expectations and subversions of them. There’s a soft side and a rough side to the woman in this piece. She has a stoic expression– not giving anything away, almost painfully emotionless. The side profile is really interesting to me, too. We won’t look at her straight on. She won’t let us.

She’s being strong through this pain, and seeming to try and show that off. I can’t tell if she’s performing grief, or hiding it, or trying to balance the two. Hiding the real and performing the palatable? I definitely see the stages of grief in this, though. She’s holding her own arm down, too. She’s balancing all these sides of herself– holding her strength and intensity back.

I think it’s interesting how reminiscent she is of Rosie the Riveter, too. I don’t know quite how that relates, except that it’s emphasizing her power! The stance is just… powerful. With the dress/top part, it’s kind of odd because it doesn’t even fit into the idea of stages of grief. There’s this other side of her, too– maybe moving on? But she can’t let that happen entirely.

Imponderabilia ; 1977 AD ; Bologna, Italy ; Performance piece

This is such an odd piece of art to observe. We watched a video of the gallery, and it took me a minute to figure out what was going on– that visitors were walking between two naked people, staring at one another in a narrow archway. It’s uncomfortable– awkward, intrusive, intimate. I kind of love it, though.

It’s challenging us to decide– quickly– what is the most comfortable way through, and then to think about why it is for us. Did you walk slow or fast? Facing to the side or forward? Which way did you face? Did your heart beat faster? From fear, or thrill?

I think the gender aspect is really interesting. Do you face the man or the woman? It seems like most people faced the woman– found her less threatening or uncomfortable– and I’m curious why. I probably would have as well (assuming I didn’t walk straight through), as her body is more familiar to me. There’s more comfort and understanding. Also, I just want to avoid feeling and generally experiencing the guy’s dick as much as possible. But even more than that, I wonder why the men chose to face her. Is it fear of being seen as gay? Is it wanting to see a woman naked? Is it that the taller ones don’t have to look at her?

It’s curious, and striking. I love this piece, honestly. It’s obviously a controversial work, but I think it’s important and thought-provoking.

Self ; 1991 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 208 x 63 x 63 cm ; Blood (artist’s), stainless steel, Perspex and refrigeration equipment

This is such an odd piece. It’s made of blood, which is so creepy, and looks like it’s peeling at every corner of the face. The fact that it’s blood is interesting because that means it’s living, sort of– decaying and decomposing. That brings to life questions of mortality. The nostrils almost look like they’re stuffed with tissue or something, and the ears look sort of fucked up in a weird way.

Initially, the feeling I got was that it’s reminiscent of chronic illness– peeling skin, discomfort. It’s very visceral. At the same time, the fact that it’s made of blood makes it feel more intense than that. More violent. I honestly don’t know what’s going on with it, though. The head looks so peaceful for its context. Maybe it’s the one perpetuating violence, not experiencing it?

The fact that it’s being preserved in a little fridge adds another layer. It’s on a sort of life support. It brings to mind medical advancements, and questions of whether they’re really advancements. Even questions of respecting one’s wishes vs. trying to keep them alive. How do you respect autonomy when it’s so painful to do so? What do you do when those two don’t coincide?

The piece also reminds me a little of “Head of a Roman Patrician,” which we looked at earlier this year.

I can’t tell what meaning this is supposed to have, or if it’s more just meant to shock. I don’t know what’s up with it. It’s pretty cool, though. Not my favorite, I don’t think.

School of Beauty, School of Culture ; 2012 AD ; Chicago, United States of America ; 274 × 401 cm ; Acrylic and glitter on canvas

I love how lively this piece feels! I can hear the chatter, the music, the confidence of the room. It seems to be a beauty parlor of some kind, but there’s more going on here than that. Everyone’s dressed in different kinds of African patterns, and they look so proud.

Across the mirrors in the room, you can see signs that say SCHOOL OF CULTURE and SCHOOL [] -UTY, though I’m not sure what that second one’s supposed to be. It gives this an extra level– that there’s not only community here, but learning. Maybe intergenerational learning?

There’s a weird white lady’s face stretched across the floor, which reminds me of the memento mori skull in The Ambassadors (also felt weirdly out of place there). The little boy is looking at it and reaching for it– ignoring all the rest that’s going on, which is interesting. There’s something particularly appealing to him about the white woman, even in a room full of Black joy and beauty– a preference taught and reinforced by society. The little girl, though, is looking up to other Black women, still while reaching for the white woman with her other hand. It feels similar.

I think it’s kind of cool that we can see the artist in the painting– taking a photo in the center of the mirror. It’s really beautiful to me that he paints himself as part of the painting, the culture, the community. He’s not documenting them from outside.

This piece reminds me a lot of Faith Ringgold’s work, too– specifically Dancing at the Louvre.

DRAWING RESTRAINT 9 ; 2005 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 92.7 x 289.6 x 203.2 cm ; 35mm film transferred to video (color, sound), polycaprolactone thermoplastic, aquaplast, self-lubricating plastic

This is so striking and surreal. I love the way the two figures are leaning into each other as they kiss– knives in hand, which should signal betrayal, but it doesn’t feel like it is, because they’re not really trying to conceal them.

At first glance, it almost looked as if the man was holding the limp body or just fur of a fox/wolf/other creature he had killed. The way the fur drapes around her makes it feel almost as if she’s an animal/mythical creature herself. She doesn’t feel real– more like a dream, or an apparition, or just a beast of some kind.

It makes me think of Shinto tradition, actually– maybe kitsune? I can definitely see the Japanese influence, of course.

Her headdress and hair are really interesting, too. The aesthetics feel almost like dry nature– whether in a desert, in the winter, or in some sort of tunda. She feels symbolic of death in some way. I can’t quite tell what’s going on with his outfit; it’s all black, seemingly kind of silky, and has a sort of interesting collar.

Also, the background– I have no idea what’s going on with it. In my mind, it feels almost like a zoo enclosure. There’s concrete all around them, and the white floor below them feels almost like ice or snow. I can’t tell what the rope/stick/pole thing is, but it evokes a dead tree for me. I think I’m just imbuing it with that animalistic energy I got from this piece. The idea of it being a zoo enclosure, or even just an enclosure of any kind emphasizes restraint, to me.

They’re soaking in something, actually. I can’t tell what. It looks oily and gross– like sweat, but pooling as if it was blood, rushing out. Could it be dried blood? It feels way too watery for that, though. It almost looks like they’re melting or rotting into the floor, like the way decomposing matter often gets mushy and wet. It also makes me think about how people’s bladders release when they die. I can’t fully tell what’s going on with it, though.

I’m thinking again about the knives. I love that they’re holding them so openly. There’s a sense of danger, but also understanding. No one’s trying to hide or pretend. There’s passion and necessity involved. Again, very animal– wild, instinctual. At the same time, there’s restraint. They aren’t just killing each other, or harming each other, or whatever else. They’re sitting still with their knives, and embracing each other tenderly– kissing slowly. The idea that they’re resisting this sort of animal nature to kill one another– for food, life, etc– is really interesting.

White Hero ; 2013 AD ; Tokyo, Japan ; 300 × 240 × 10 cm ; Acrylic and automotive paint on aluminium

I’m really overwhelmed by this piece. It’s beautiful, and I have absolutely no clue what’s going on. It seems very turbulent, like a fight scene– with this one woman in the center. I can’t tell if she’s strung up/captured or just standing up (it seems like the first), but she almost reminds me of one of the Sailor Guardians! Maybe in mid transformation?

Like I said before, it looks like there’s some sort of fight going on. The huge black thing seems like a great dragon of some kind, but it also looks inspired by a scorpion or some kind of bug. The blue at first made me think of water, but the way it wraps around the girl’s ankles and the dragon’s neck makes me think that maybe it’s more sentient? I do think it’s probably water, but it’s cool that it has a life to it.

It’s taken me so much looking to figure out what the white creature is, but I think it’s like a person diving down into the fight with a spear. It reminds me a little of hollow knight, or even just any fencer.

I love the chaos. It feels so wild & free & fantastical. I don’t have too much to say about the piece, to be honest, but it’s really cool to look at.

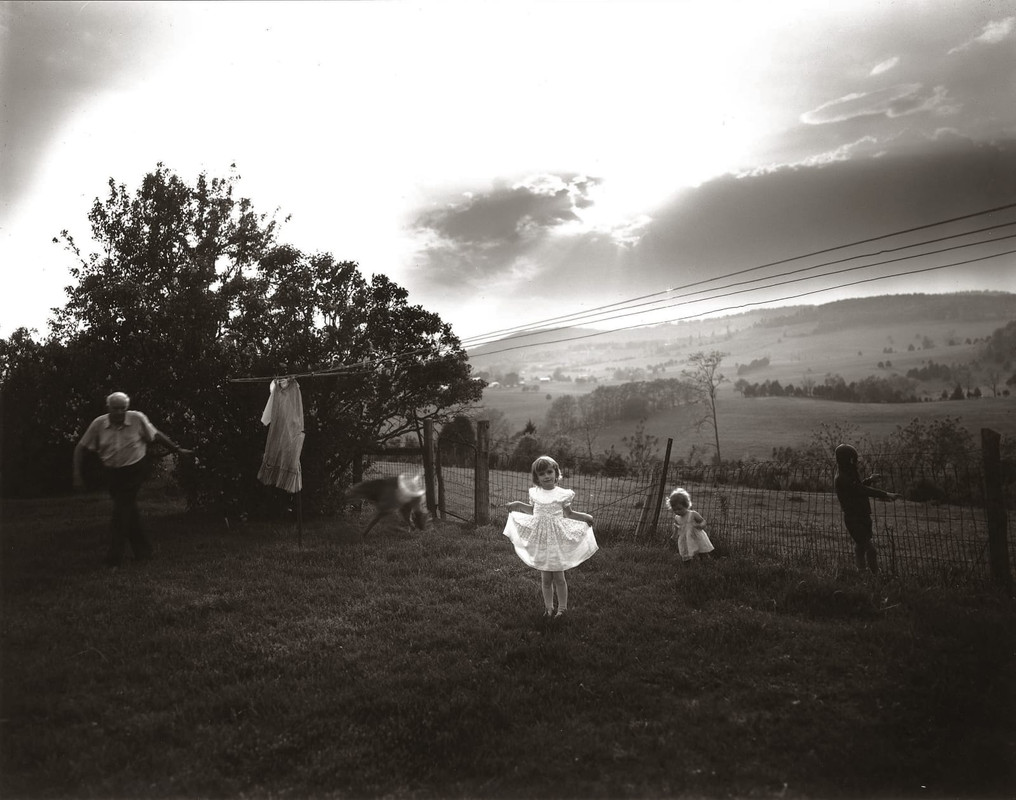

Easter Dress ; 1986 AD ; Lexington, United States of America / New York, United States of America ; 50.6 × 60.4 cm ; Gelatin silver print

This is such a cool and eerie photo. It feels almost like it’s from a VHS tape sequence in a horror movie.

The little girl is showing off her dress and herself in a really sweet and innocent way. She seems so proud and excited to be in something she finds beautiful. The black and white makes it feel more off-putting, though. Especially with the (obviously empty) dress hanging on the clotheslines, the other figures along the fence, and the old man moving toward the camera on the left side.

I get a sense that it’s exploring innocence vs. something more sinister. I don’t know who the sinister side is coming from– definitely not the little girl. Maybe the photographer, or some other adult? The old man on the left?

It’s an interesting piece. I honestly don’t have a ton to say about it– it just feels weird to look at.

Judith and Holofernes ; 2012 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 120 x 90 in ; Oil on linen

This piece is gorgeous. I’m enamored with all the bright colors, the powerful & intense look on the woman’s face, and the fact that the head she’s holding looks down. Floral patterns dance through the background, leaping across her dress, and add an intensity to the piece. It’s dynamic, glam, and strong.

It’s obviously very provocative in the modern landscape to create art that features a Black woman holding the severed head of a white woman. To me, this calls back to accusations of ‘reverse racism’ that often come up when we discuss the violence caused to victims of oppressive systems and resistance against this violence. It reminds me of ‘white woman tears’, too, as a victimhood complex often weaponized to punish those that speak out against aggression– micro or macro.

At the same time, I think in a literal way, it’s still really cool to see a Black woman portrayed with so much power, and holding the head of someone who is naturally perceived to have power and superiority over her. I’m curious about the context of the story, in that regard.

I also found it interesting that they included that natural motif in the background; it feels like it emphasizes ideas of a sort of competitive, dog eat dog world, and even survival of the fittest. I don’t think it necessarily means that in a literal way, but it does inform it. It’s also interesting since flowers are usually perceived as feminine and meant to represent fertility.

Dysfunctional Family ; 1999 AD ; London, England ; 58.25 x 20.5 x 15 in ; Wax-printed cotton, polyester, wood, plastic

These creatures are so odd and interesting! I don’t know where to begin. Their faces and poses are very endearing (I particularly love the eyes), and they’re so vibrant and lifelike. They almost remind me of Stitch (of Lilo & Stitch fame) with how sweet they feel.

I’m intrigued by the fact that the color combinations are two and two. It almost made me feel like there are the ‘girl’ ones– maybe a mom and daughter– who intuitively seem to be the yellow and red, with more feminine proportions and eye shapes, alongside the flower-like pattern, and the boy ones, who’re sort of lanky and awkward-looking.

The bodies all have sort of emphasized breasts and stomachs, which is interesting to me– particularly on the blue ones, which is interesting because they did strike me more as male originally. They get a bit of humanity in that way, too. I suppose, then, that it’s likely they’re meant to be women. I just can’t really make myself see it like that, though.

The tall blue one makes me giggle a little bit, with his puffed out chest. I will say that I don’t think the parents are the tallest ones. In my head, the two on the left are the parents, and the ones on the right are the children (the daughter being a teen, and the son being a little kid). I know it makes more sense that the tall ones would be parents, but the short yellow one reminds me so much of a maternal, grandma-like figure.

It could also be two separate parents letting their children play? In which case, the smaller yellow one would likely be a kid.

I’m curious about the color and pattern choice. The patterns also seem to have African fluence. The flowers on the outer edges of the eyes of the small yellow one reminds me of makeup, and makes it feel more mature.

I think it’s interesting that I saw these bright mosaic-looking (is it fabric that looks like mosaic?) creatures and immediately assigned familial roles and gender roles to them. Humans have a bad habit– though, of course, an understandable one– of being unable to see the world outside of our own societal constructs and ways of thinking, and I definitely feel that looking at this piece. I recently learned that pill bugs have separate neural ganglia in each limb that react entirely separately and very mechanically, and that was just entirely impossible for me to conceptualize. This called back to that in my mind. I can’t help but perceive them as ‘us’ but transformed, perverted, etc.

Also, they remind me a lot of bugs! Kind of like ants? Which is very fun, too. I don’t have any commentary on that; I just noticed it.

Generally, this does seem to highlight similarities and differences between beings (family?) as well. It’s fun to me, and the whole thing feels playful to me. You could extrapolate some more political commentary there than I already have earlier in this, but I don’t really want to? This piece makes me want to just enjoy it and have fun with it. It doesn’t feel like it needs to be very intense and serious, even if it is making some (cheeky) commentary.

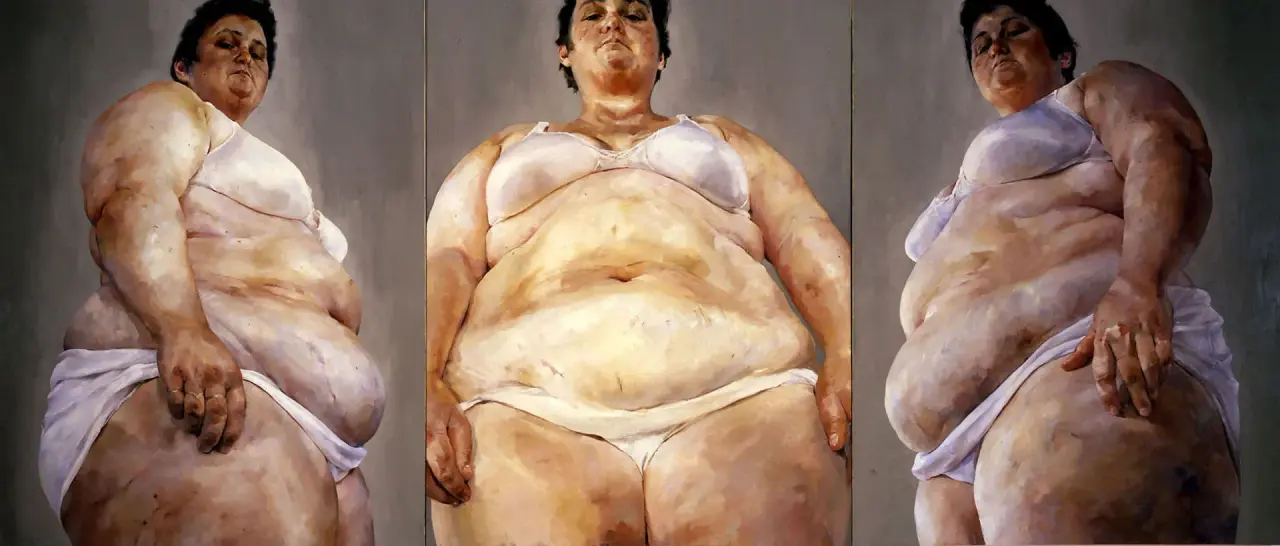

Strategy ; 1994 AD ; London, England ; 274.32 x 638.81 cm ; Oil on canvas

This piece is really striking to me. The woman in the painting looks down at the artist/camera/whatever with a look of disdain, frustration, disappointment, or maybe just seriousness. It makes us feel small as the viewer.

The colors are very dismal, and the artist chose to emphasize her rolls and discoloration, which is interesting to me. In the middle panel, there is some other lighting, though– a little bit of warmth.

It’s interesting because this feels like a very vulnerable position– almost naked, totally exposed, and from a lower perspective which is often dubbed as unflattering. I love that she doesn’t seem afraid or vulnerable, though. The fact that she’s looking down on us makes me feel like she’s sort of judging us for our judgments– commenting on the intense scrutiny we put on others’ bodies. She’s challenging us to comment on her, asking us to just say it. The fact that there are three of her adds to the intensity of that.

At the same time, it reminds me of body checks; there’s an interesting factor of self-judgment and internalizing the hate the world generates as well. It’s like a little progress check. I look at this and get a feeling of both frustration at the rest of the world and yourself for this hate.

Could she just be showing herself off, though? The fact that she wasn’t painted in some sexy, extravagant lingerie makes me think that’s not quite the purpose, but she is definitely gorgeous, and isn’t ashamed in any way.

I have many more thoughts, but don’t know how to put them together. I love this piece, though– a lot.

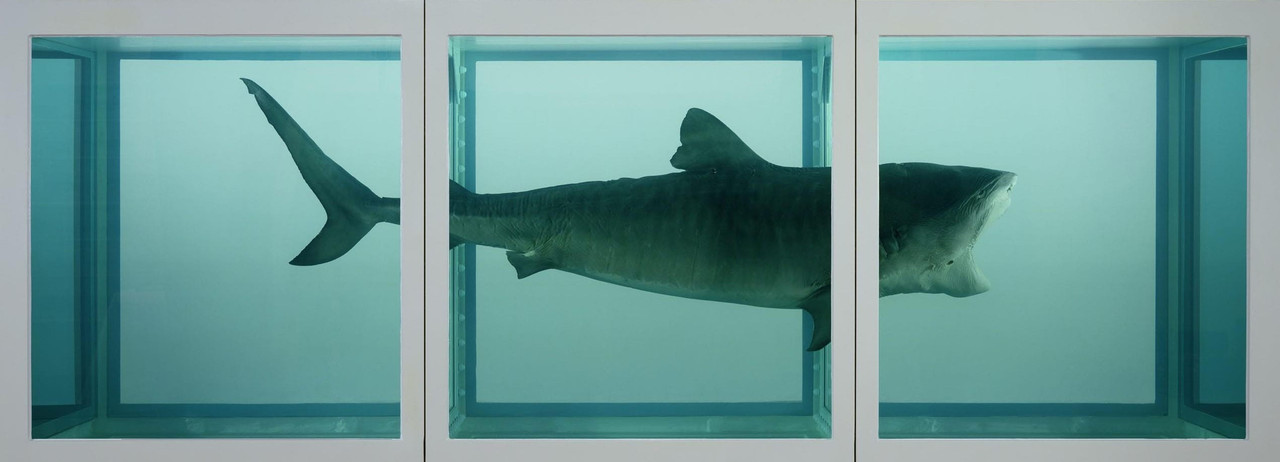

The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living ; 1991 AD ; London, England ; 213 × 518 × 213 cm ; Tiger shark, glass, steel, formaldehyde solution

This piece makes me incredibly uncomfortable. The shark’s jaw is open, but it doesn’t feel very scary for some reason? We associate that open jaw with action, but I don’t see any; it’s so still, it’s almost uncanny. Probably because the shark is dead (if it’s real). When I look at it, I get more of a feeling of despair; its jaw is held open, even if it’s tired, and the cage around it holds it in. It almost reminds me of how your mouth gets kept open at the dentist. It’s like it’s being examined– set up to be observed. It might be more terrifying in person, but I don’t know. I just feel sad and disturbed.

It feels so sterile– almost reminds me of a hospital, though the body is being preserved in death (fresh death, specifically) and not in life. If it’s well-preserved (or meant to be preserved at all), then I guess you don’t get to watch it decompose, but that could be interesting if you do get to. It’s interesting that the cage is partitioned into three, calling back to triptychs. Also, cutting off the tail and head makes sense for how you deal with caught fish.

I will also say I’m curious about the choice in shark specifically. Sharks are often symbolic of strength, survival, determination, protection, etc, which definitely says to me that it’s commenting on life and death, and maybe even the way we treat the life around us, but I also feel like it’s sort of misplaced if this was a real, live shark. If it was, then sure, there’s a chance it was found and preserved, or simply taken from a place like an aquarium to be used as art once it died. But I don’t quite buy that, to be honest. It feels less probable.

The fascination, examination this creates is intense. It’s morbid, and absolutely makes me contemplate life and death. If it isn’t a real animal, I’m more intrigued. There’s more room for commentary on markets around animals, trophy hunting, etc.

I’m trying to gather my thoughts on this. It definitely is confronting life and death, regardless of how, but I don’t think I like the art– particularly if it’s a live animal as I expect it is. I’m thinking about how expensive ‘fine art’ is, and how much this sold for. Was it worth it, to hold death in your home or wherever you’re going to display it? Is this ethical? I feel like it’s not. I do think this is successful, though, in some regard; it makes me feel something, if not what he intended.

Kui Hua Zi (Sunflower Seeds) ; 2010 AD ; London, England ; One hundred million hand painted porcelain seeds

It’s genuinely so shocking to me that someone could make and paint so many little porcelain sunflower seeds. I can’t imagine how impossibly long that would take, and how difficult it would feel. I feel like I’d start to feel like Sisyphus after a while– especially if I got to watch all of them sort of blend together into a gray mass as I continued on.

To be fair, I doubt the artist made them all themselves. As with a lot of these artists who do projects of huge scale, I imagine he has a team.

When I heard about sunflower seeds, I thought pretty immediately of my grandpa who loves to snack on them– he always has a bag ready to devour. It also feels sort of communal, because it feels like a very shareable snack. It’s sort of interesting to have something be directly both a snack and a literal seed of life, meant primarily to reproduce. Then, it can’t really sprout life; there’s no room for them to grow and become new and different (like the people sitting in the room) because they’re porcelain! There’s a sense of uniqueness and also sameness.

There’s so many different ways to read this piece– a room full of potential life, yet monotonously gray, or a room full of seeds to share and eat and lay in. It almost looks like snow, sand, or gravel– comfy and odd-feeling. It’s very uniform, simple.

I’m also thinking about sunflowers themselves, now. The way they turn toward the sun is so direct and obvious; they know exactly what they need, what nourishes them. There’s a very deep personal understanding and connection with the world around them.

The colors and feeling of the sunflower seeds mismatches so much with all these ideas and memories I have swirling around them. It’s gray, simple, the same everywhere. They all took so much work, time, and love, but they’re lost among this greater mass. Everything blends into one being.

I’m thinking back to the fact that the artist likely has a team, too. There’s community and shared experiences, and yet it’s all lost to this sort of great project, and even to the main artist who conceived of it. In the end, it’s still viewed as the artist’s project alone.

Preying Mantra ; 2006 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 186.06 x 137.8 cm ; mixed media on Mylar

I’m really amazed by this piece. It’s so ethereal and gorgeous, and I don’t know quite where to begin. Our central figure is lounging playfully in the limbs of a tree— almost trickster-like or seductive. I feel like I’m being invited to play— to guess what this piece is trying to say. It’s begging me to misinterpret it— to dare to.

The body and the space around are both a collage— literally and figuratively. On their body, I love the sort of watercolor look— almost like the pattern of light in water. It’s dappled by sunlight, and it sort of camouflaged with the tree and its leaves behind her. They’re hidden away— a chameleon, and fairy-like. Also, they’re very androgynous; it’s interesting because they have a beard but also have positioned themself in a very “feminine” way. I love it.

I can’t tell quite what’s going on with their neck and behind her head. The thing by their neck feels almost like a spine, but also looks like a pitcher plant or maybe an insect, and the thing behind their head looks sort of like a bird. Her colors and patterns feel like an orchid mantis, too. Is she dangerous? The way the bird overlaps with their head is interesting to me— a sense of flight, peace, divinity in mind.

I love the way the patterns blend together behind them. There’s two main ones that meet each other at this sort of horizon— black, yellow & white patterned hills meeting the pink leaves & yellow sky behind them. It all feels like it’s moving— churning beneath & behind them. Actually, are the hills meant to be a blanket? This makes me question if they’re hanging in the trees at all or if she’s on the blanket. The perspective is odd, so I think I was wrong at first; it looks more like they’re on the blanket with the trees sort of wrapping toward her.

Regardless, the way the blanket/hills meet the leaves and sky makes me feel like there are two worlds colliding. Because of their sensuality as a figure, I’m getting themes of civilization and nature, nature and gender or sexuality, even just society vs. society. I’m not sure— it feels like it’s trying to explore clashes, but then the way overlap & ambiguity exists even still in clashes (with the shared colors between both sides). That also feels supported by the ambiguous gender. The fact that they used a cultural cloth (African, I think— maybe Southern?) beneath them also adds a question of culture and ethnicity for me. The fact that they’re laying back onto cloth is like it’s supporting them, but they also have their hand behind their head, supporting themself.

Stadia II ; 2004 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 108 x 144 in ; Ink and acrylic on canvas

There’s so much going on in this piece; it’s really interesting to me. I don’t know that it’s actually physically big, but it feels like it should be in the same way Rothko should always be huge— overwhelming, all encompassing to your vision. I want it to be wall-sized or larger. I want to have to crane my head to see every little detail— feel like I’m there.

Right away, it reminds me of a stadium, covered in flags and banners, but as if a tornado hit it (ha). Maybe a political chamber space, like for the UN? The lines that make it feel like one of this grand, auditorium-style structures also sort of emulate a tornado, especially with so much chaos surrounding them.

If it is a stadium of some kind, then I can understand the chaos as emulating the loud cheering— happy and angry alike. If it’s a chamber, it could be emulating the arguments & frustration that comes with those conversations. Maybe it’s not just a chamber with only politicians, but like… a political event with a crowd. It could be a performance space of some kind but I just don’t really get that vibe with the chaos & celebratory feel.

I’m curious as to why the artist chose to depict this kind of situation. In any version, there’s a lot of chaos, but I also feel like there’s a sense of commitment to your beliefs & history & culture here— party lines, countries, teams. It all sort of mimics the battlefield with strong nationalist sentiments and hate of the other for whatever reason is imagined. Commitment and love for your people can be beautiful, but this feels somewhat more doomed in my eyes, even with all the excitement.

There’s little dots in the center that feel like they highlight things. Yellow spotlights shine down the middle, and the smaller dots feel like confetti or maybe just other people (is it the ‘losing’ team or politician or whatever, or maybe some otherwise important people). It’s hard to tell what’s what because I don’t have a sense of depth here. There’s a ton of different perspectives and overlapping messy ideas— especially with the charcoal (?) smudges. They feel almost like little plumes of smoke, though I don’t know that they are.

Also, on a personal level, this got me thinking about the upcoming Olympics and the chaos of it. It’s beautiful and exciting, but also sort of terrible in its effects on the surrounding areas— particularly the homeless encampment sweeps that already happen too much and will increase in frequency. There’s excitement and something sort of apocalyptic/dystopian.

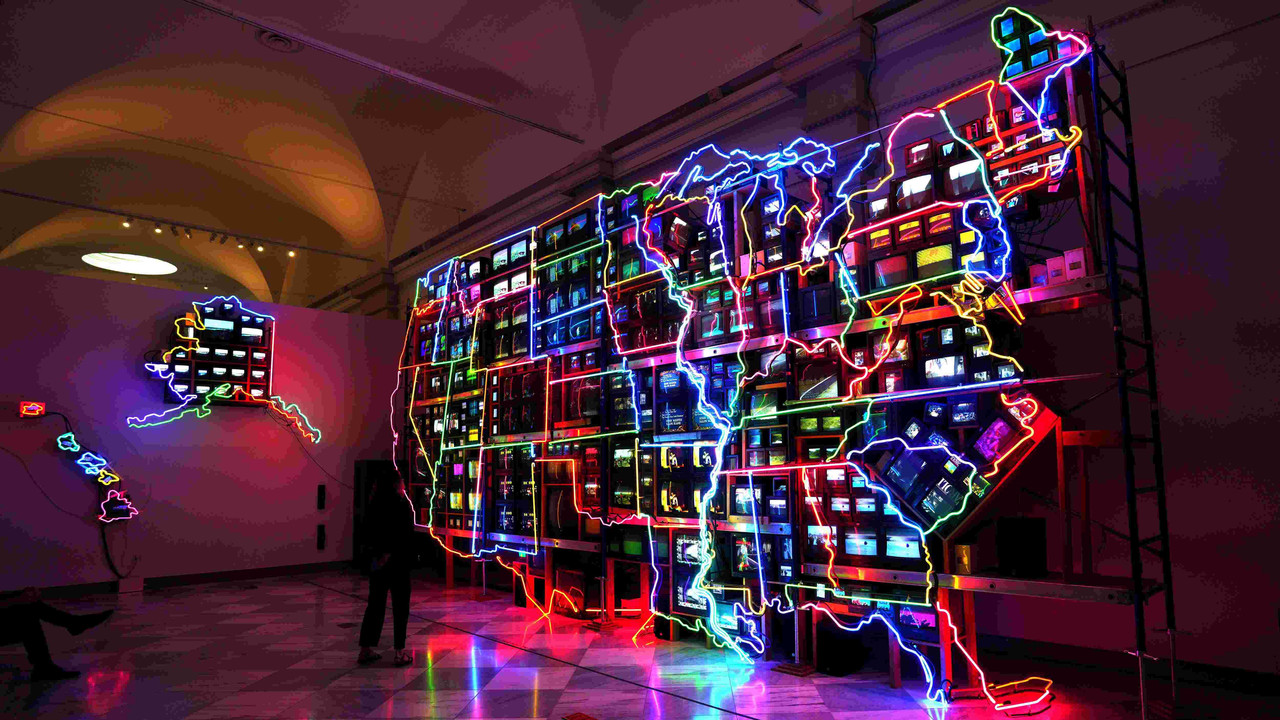

Electronic Superhighway: Continental U.S., Alaska, Hawaii ; 1995 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 15 x 40 x 4 ft ; Fifty-one channel video installation, custom electronics, neon lighting, steel and wood

I’m very amazed by this piece. It’s massive and loud— a neon-lit, flickering map of the U.S., buzzing with TVs and electric light. There’s something hypnotic about all the blinking images, overlapping sounds, hum of electricity. It’s flooding your senses with information, exactly how the internet does. It also feels a little sad and tiring, though, like being online or simply staring at screens for too long.

The shape of the U.S. is mapped out in glowing neon tubing, each state framed in color, and each one has a cluster of televisions playing videos inside. They all seem to be specific to their states— clips of moments from their histories, symbols that’re commonly associated with them, or literally just videos of places within them. They have their own mythologies and cultures.

This piece definitely feels like a product of early internet to me, like a warning or a prediction— already imagining the internet as a kind of sprawling, overwhelming thing. It’s a grid of images and signals that connects the whole country but also drowns us in the process. With the start of the internet, there was this push to believe in tech as this unifying force, but this piece doesn’t feel optimistic. It feels chaotic and disconnected. Even though it’s all one piece, the TVs don’t talk to each other. They’re loud but desperate, in their own little boxes.

It also makes me think about the internet as a literal information highway, which was a term that’s definitely thrown around. It’s funny now, how that’s exactly what happened. Travel happens online— not necessarily in the physical world.

Also, a lot of the images in this piece are of the press, which makes me wonder if it’s also a political commentary of some kind— describing the way we’re overwhelmed with information by different biased sources, all clambering for our money and attention. I’d have to think about that more. It definitely feels like it’s a commentary on capitalism in some regard— yes, primarily about the internet, but also just about how everything wants to capture us as a product. We’re being sold to and used.

Generally, the colors are garish and artificial— neon pinks, greens, blues— almost like Vegas signs or cheap motel lights (which also feeds into that capitalism commentary). It gives the whole piece this mood of a performance, like America is putting on a show— for others, but also for its own citizens. We’re watching it on repeat— letting it ensnare us, trapping ourselves behind glass screens. Parts of it are beautiful and wonderful, maybe, but it’s also sinister and sort of exhausting.

Dancing at the Louvre ; 1991 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 73.5 x 80 in ; Acrylic on canvas, tie-dye, pieced fabric border

I’m immediately amazed by both the bright and beautiful colors and the fact that this is a quilt! It depicts people (a family?) dancing in the Louvre, showcasing some paintings that also seem to portray families behind them. It’s a really gorgeous piece, and the strong colors & flowers on the edges make it seem so vibrant and bursting with life. There’s writing across the top and bottom, too. It’s interesting to see this family of Black people dancing in a space that tends to be treated with ‘reverence’— quiet observation— and embrace European art & identity, mostly casting others aside. In that way, this piece is letting its characters break the rules, and it’s breaking the rules by depicting them. They’re centering their own joy, art, and selves in a deeply Western space. They’re sort of rewriting the story of Black people & art.

I think that this could be a direct call-out to the very white supremacist culture of art, especially at such a ‘high’ level. It’s exploring the importance of Black people finding themselves in art even if it’s not already presented for them (with the reflection of the family in the depicted art, which should be reflecting but isn’t quite because of the whiteness) and in just experiencing it at all! But it also feels like it’s just trying to tell a single story— not a general one. This is one woman, a few children. They’re finding their place in art and in a white world in general, and this is just holding space for that. Maybe the writing along the bottom and top imply that specific story/narrative?

I’m curious as to why the artist chose the quilted medium. To me, it feels really sentimental, generational, and even maternal— like history & skills being passed down through mothers & daughters. It’s an act of care. I find it really beautiful, regardless. It’s kind of cool to me that you could literally wrap this story around you.

Pink Panther ; 1988 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 104.1 x 52 x 48.2 cm ; Glazed porcelain

I’m really interested & confused by this piece! It looks almost like a small figurine, though the fact that it only features part of their bodies makes me think it’s probably much larger.

We have this very skinny, blonde white girl in a super tight & revealing dress— covering her breast with one hand and holding the pink panther with the other. At first, I wondered if the pink panther was just sort of awkwardly being held, but the fact that his tail sort of wraps around her hip makes it feel like there’s some possession on his end. It adds this extra level of perversity to it for me. It’s also interesting to me that the pink panther seems so tired; I wonder if this is an expression of Hollywood’s fantasies? Both her & this cartoon are essentially made up for entertainment. I want it to be a critique on consumerism– that we should be ‘happy’ with all that we have, and yet we remain sort of hollow & unsatisfied– but I honestly just don’t get that vibe from the piece. It makes sense logically, and yet I don’t think that’s quite what it’s about.

The colors palette also seems quite old— almost out of a 50s or 60s catalog. I’m curious if this is a parody of works that are sort of nostalgic for a time with less progressive thought, or even if it’s just one of those pieces. It feels like it intends to be provocative. The dress defies physics for the purpose of revealing her body (unless it’s a mermaid tail or something), and she has this incredibly brilliant smile. At the same time, this sort of sexual symbol is paired with a very childish figure— a cartoon! The pairing, and this piece in general, could be sort of insulting to a random viewer. It feels unnatural and like it’s happily reveling in something very wrong.

The Gates ; 1979-2005 AD ; New York, United States of America ; 7053 gates, 23 mile path ; Steel, nylon, and vinyl

I’m enamored by the brilliance of this piece— particularly in the photo I’m looking at, surrounded by barren trees, gray skyscrapers, and a frozen lake. My guess is that this is in Central Park, but that’s pretty unfounded— the photo just seems similar to photos I’ve seen. If it is, I think it’s interesting because Central Park has an appeal of being an escape from the city into nature; would locals like it? I guess that they might not, though personally I think public art + nature is a very exciting and lovely combination. It’s especially interesting in winter, when people might not be going out and the nature isn’t as traditionally gorgeous. I’m curious if it was a temporary installation (which I feel like a lot of public art ends up being), because then it being in winter is especially important. The piece seems to be lining a lot of pathways so if you were visiting, you might walk through it a lot more than you usually would.

I’m curious how many of these orange gates there are, with their long curtains. Why so many? The curtains seem to end at a really tall height, too; it’s not like we could pass through them while we walk below the gates. They’d just dangle above us. Since the curtains are cloth, I feel like the gates would add a lot of warmth to your walk in the park— especially with the way they float above you like a sun. Photos that show them in the light are beautiful; I adore the way the real sun catches the cloth. It adds this brightness that feels unnatural and natural in different ways.

I’m trying to imagine different people experiencing this art, and I can totally see myself as a little kid, running through them all, treating them like fairy portals to explore. Even as an adult, I think there’s a certain element of transition & new beginnings that comes with walking through a door or gate; it could feel sort of overwhelming but also renewing to walk through so many. I think that’s especially true because it’s winter and soon to be spring, and there’s a lot of rebirth that comes with it. Maybe it could act as a sort of cleansing ritual? I could also see this bringing a lot of renewed appreciation to the park, especially if it was a temporary installation.

Tāmati Wāka Nene ; 1890 AD ; Hokianga, New Zealand ; 101.9 × 84.2 cm ; Oil on canvas

I got the impression right away that this was a portrait of someone powerful— maybe in war, or in governing. Their stance and expression just sort of exude strength to me. The person has traditional Māori ‘tattoos’ which are called moko and meant to represent personal identity and heritage; his are full of spirals that kind of evoke nature (especially when paired with the background being nature and his outfit being full of natural materials). At the same time, the art style is pretty traditionally European, which makes me think they are a Māori chief who’d be involved in diplomacy with the British. Could the person depicted be one who sided with the British? But then I wonder why they’d be depicted with such traditional clothing and expression, and not as more assimilated into whiteness. More than that, though, I imagine it was painted by a European who had some amount of reverence and respect for the person’s culture and self; they might be particularly intrigued by the culture.

He seems to be wearing a very large cloak made of feathers (maybe of a kiwi bird?) alongside some turquoise/jade/greenstone earrings. I’m curious if these have any cultural significance or are simply decorative or a show of status & rank (having nice things). I’m intrigued by the staff, which also seems like it could be a kind of blunt weapon— something that especially would make sense as a show of poetry. It’s adorned with some more feathers and has a little carved hand grip with an eye that I’m guessing is made from abalone.

I love the colors in this piece— everything seems to be reflecting off everything else. The sky is shown in their skin, and the colors are striking yet muted.

I really love this piece, honestly, and feel mostly intrigued by the context/use of this painting. Is it meant to remember him? Is it propaganda? Is it cultural or political?

Chairman Mao goes to Anyuan ; 1967 AD ; Beijing, China ; 220 × 180 cm ; Oil on canvas

This piece feels almost mythical— like it could be depicting a scene of an epic of some kind (the odyssey, beowulf, mahabharata). Obviously this is depicting a man walking, but it also seems to be depicting the idea of a force moving through the world, striding down from a perfectly blue sky. The fact that he’s above the clouds, too— seemingly exploring the tops of mountains— makes him seem like he’s descended from another realm. The mountains also seem to represent strength in my mind, which places him among them.

It seems like propaganda to me, especially as i’m pretty sure it’s depicting Mao Zedong, but also because of this positioning. He’s young here, idealistic, standing above the landscape rather than within it, as if he’s literally elevated by his vision. At the same time, he seems to have overcome the obstacle that is these mountains. His stance is strong and confident, as if he’s pushing forward because he knows it’s necessary. The colors feel deliberate, too— particularly the choice of red in the umbrella (associated with luck, the communist party, and warding off evil) and the path in front of him which symbolizes, I imagine, the world he’s walking into. This also contrasts against the very pastel, peaceful, ethereal background. I’m intrigued about the umbrella/parasol. It would make more sense conceptually as an umbrella (preparing to shelter against difficult weather & resistance), but I also think it sort of has to be a parasol based on looks. I just can’t quite understand the symbolism there.

His clothes are simple— not very ornate— but still quite nice. He’s impressive, but not disconnected— a worldly man despite the insinuation of leadership and status in this portrait. Maybe it’s the clothing of a scholar or politician? That choice, though, feels similar to the fact that he’s been put in nature, in order to imply his connection with the world around him.

Generally, though, he seems sort of untouchable— determined with a closed fist and a concentrated look. It reminds me a bit of old religious paintings, where saints stand just a little too still, glowing— their expressions too serene for real life. It’s not about capturing a moment as much as it’s about shaping a legacy. At the same time, it’s super realistic! It’s not trying to totally depict him as other and different. It feels like a court painter’s work in Europe.

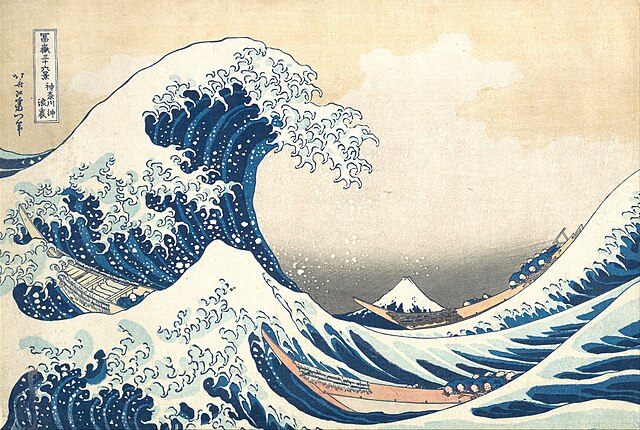

Under the Wave off Kanagawa ; 1831 AD ; Edo, Japan ; 24.6 × 36.5 cm ; Polychrome woodblock print, ink and color on paper

This piece is so incredibly famous, it feels hard to really look at it. My brain just goes “oh yeah, I know that one– moving on” and tries not to look any deeper. But I do feel that, forcing myself to really look at it, I’m hit by how actually huge this wave is. It seems alive, curling in on itself– barely holding together before a collapse. It seems clawed and hungry, but also sort of slow– so enormous, it can’t move any faster. There’s such a tension in this moment before the crash.

Mount Fuji is so small in the background, it almost disappears. Obviously, to some extent, it’s just about perspective, but it also definitely tricks your brain for a second. Is this wave that big? Just maybe. And the mountain is a symbol of permanence and stability, but it looks delicate and is somewhat forgotten in favor of the chaos in the foreground. At the same time, it’s sort of untouchable. It’s far, and no matter how violent the waves get, it will stay standing. There’s almost a theme of perseverance here.

The boats and the people in them add to that. Three long, thin boats– fragile-looking, too– that are riding the waves as if they’re a part of them. The fishermen inside are only slightly visible– hunched over bracing themselves and seeming almost exhausted in the vague impression of faces that they have. I’m intrigued by the choice to paint their clothing in that beautiful Prussian blue, too. It gives them a sense of unity with the chaos they’re enveloped in; yes, they’re victims of it, but they’re also part of it. And the golden ratio in this piece makes that even stronger. Everything here is wrapped up in the rest. They also don’t seem to be trying to escape (even if it would be hopeless to try)– embracing the danger and pushing forward. It’s necessary!

The print seems to be a woodblock print, likely from the Edo period? Essentially, this isn’t one of a kind; it’s reprintable, meant to be experienced by regular people. It makes sense that a piece like this– beautiful and striking, yet speaking to the perseverent values of these hard-working regular people– is something they would want in multiples! Also, Edo-period Japan was relatively isolated from the world– peaceful, yet under relatively strict rule– so I can imagine pieces that explore new places (and travel destinations like Mount Fuji) alongside maybe unfamiliar chaotic situations would be interesting.

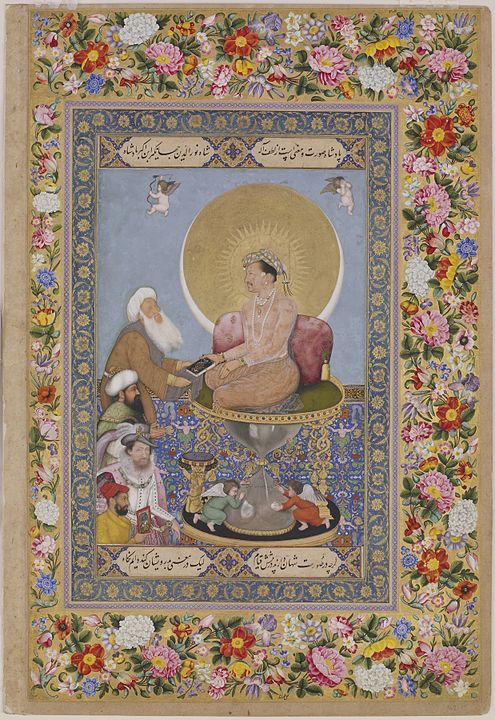

Jahangir Preferring a Sufi Shaikh to Kings ; 1615-18 AD ; Mughal India ; 46.9 x 30.7 cm ; Opaque watercolor, gold and ink on paper

The first thing I notice here is the hierarchy, how the focal point person sits on this elevated platform– literally, a giant golden hourglass haloed by a sun and moon– physically above the other figures, glowing in a halo of gold and flames. The composition is very carefully arranged, all the characters seeming to spiral up toward this moment of exchange– the seated man offering a book to the person kneeling in front of him.

I’m trying to guess at the historical context of this (channeling AP World History to help me analyze this clothing…) and want to guess that this is a Mughal piece, with the man who’s receiving the book being some sort of religious figure (maybe a sufi?) and the others being a sultan, a European who’s rich in some way, and an Indian person (the artist, maybe, since he is depicted with a painting in hand). Everyone else is below the sufi physically, though– even the European, painted with delicate realism, who honestly seems sort of offended. To me, that signals that this piece is almost entirely about hierarchy– about the main man (maybe a Mughal king?) choosing spiritual wisdom over political power. It’s absolutely some first class propaganda.

I only mentioned it vaguely here, but the hourglass takes up a really huge portion of the canvas and is a really interesting choice. Time is literally running out beneath the king, which feels like a massive statement for a king to make. This isn't just a casual seating choice; it’s a visual metaphor for the fleeting nature of power and life itself. Still, though, the king isn’t panicking. He’s above it, glowing with his sun-and-moon halo, as if transcending time itself. There's an almost divine permanence implied in his stillness, despite the fact that, beneath him, sand is slipping away. He’s acknowledging mortality while also asserting something eternal.

Below him, too, there are the tiny cherubs at the base of the hourglass who add another layer of divinity, as if he’s being supported by them. I honestly can’t tell what they’re doing, either; it seems like the one on the right is writing his name into the glass, but he also holds a jar I’m curious about. Also, why these European cherubs? Is it meant to show a sort of global influence– that he is involved everywhere?

The piece really does feel over the top in the best way. There’s an impossibly intricate floral carpet, the throne is decorated with delicate Persian-inspired inlay, and everything is edged in gold. I love how the borders of the painting are just as much a part of the art as the scene itself– flourishes of plant life, text that makes it feel like a page from a royal manuscript. It’s definitely Mughal, but there’s Persian and European influence woven into it, especially in the shading of the faces, the way volume and dimension are rendered.

Shiva as Lord of the Dance ; 11th century ; Tamil Nadu, India ; 68.3 x 56.5 cm ; Bronze

I know this piece! Very well, actually— I think my dadi has one by her bath. It’s a depiction of Shiva called Nataraja, where he is the Lord of Dance doing his divine and cosmic dance. This depiction is incredibly well-known, and in most Hindu temples. I think the common understanding is that this is the state he is in when he performs his duties of creation, destruction, and preservation.

In this depiction (and in most), he’s enveloped in a ring of fire, holding the flame of destruction in his upper left hand. His hair stretches out to both ends of the ring (seemingly representing the universe, cycles, the eternal, continuity, unity, connection) and sort of emulates a halo, and he holds a drum in his upper right hand. The fire is interesting as well because yes, it destroys, but it also has healing capabilities.

The other hands are mudras that represent things I can’t quite remember! I’m going to guess that the forward-facing hand is meant to comfort and make clear that the viewer is safe as I feel the forward-facing hand usually does, and the other hand shows gracefulness and peacefulness in his dance. He’s also balancing in tree pose, which obviously connects to the balance he is meant to uphold. Also, Shiva is dancing upon and crushing Apasmara, who is the demon of ignorance.

He looks incredibly tranquil throughout this process, which I love— a serene smile on his face and his eyes closed calmly. Even though there’s a lot of chaos involved with this, it’s like… doing what needs to be done. It’s not good or bad; it just is.

Funeral Banner of Lady Dai ; 180 BCE ; Mawangdui, China ; 205 x 92 x 47.7 cm ; Painted silk

I absolutely adore the colors in this banner. The reds and blacks make it feel so intense and important, though not necessarily bad, as red could signify good fortune moving forward and black could just be symbolic of the unknown/unknowable and even peace.

I can definitely see several layers in this piece. In the center-ish region, we see a person standing in robes, leaning upon a cane, surrounded by attendants. Underneath them, these very long dragons’ bodies are entangled and reaching toward the sky above. The sun and moon in the top section alongside this gives the impression that they’re in heaven or maybe a dream of some kind? But I think heaven is more likely, meaning that this piece would likely have some sort of commemorative or funerary/ceremonial use. If it is funerary and not just a memorial, then is it meant to identify them? Does it have a spiritual/religious role to play, like maybe the book of the dead?

Below the dragons, we see people sitting quietly (I imagine) with some vases in front of them, perhaps to hold food or some other things. Behind them, I can see a little of what looks like their robes. I’m not sure if that’s just background detail or if it’s meant to be them (their corpse?) and is either faded or just hard to see. Below them, there’s a weird creature… it’s very marine to me, like some sort of squid monster.

A lot of animals inhabit this piece— particularly the tortoise and fish with owls on their back near the bottom, and then moving upward. At the top of the piece, which we identified as heaven (or some sort of dream world), there’s a lot of sort of… mythological exploration. We see a sun (with a crow? or other dark bird) on one side and a moon on the other, likely signifying balance. We see the heads of the two dragons, and what looks like two horses with something riding them? There’s also two people who seem to be guarding the realm alongside the dragons (which are also meant to be an embodiment of all animals, sort of representing everything).

I’m honestly pretty overwhelmed by this piece. It seems to be telling a story more than making a claim about immortality during life or something. I’m not sure what its use is. If it was a funerary banner, then I’m curious about why it exists.

The Court of Gayumars ; 1524-25 CE ; Tabriz, Iran ; 45 x 30 m ; Opaque watercolor, ink, and gold on paper

I’m really impressed by the beautiful color in this piece; especially with what looks like watercolor. It’s so bright and well-placed and really draws my eye around the whole piece little by little. It’s interesting to me because the placement of the men/people reminds me of that within a court of some kind, with the man in the center sitting in padmasana in a sort of ‘throne’ and the others standing at attention all around him. That said, it clearly can’t be a literal one as they’re very intertwined with nature instead of being in some palace setting– sitting upon cliffs and trees and grasses, and among animals. The animals themselves almost feel part of this community with the way they’re placed in this circle of people; there’s absolutely a sense of unity and harmony there. Also, it’s interesting that so many people are directly lined up but there are a few groups that are separated. Is it hierarchical? It has a lot of flow and definitely feels like it’s constantly moving and changing.

Maybe it still is a court of some kind, but a mythical one? Like… if it’s storytelling, then maybe this is a king of nature (or just among and in harmony with nature). It could also be a god of some kind, though that makes less sense to me culturally if this is Islamic (or West Asian in general), which is something I assume because of the Arabic script/calligraphy along the top and bottom of the piece. I also think this script really emphasizes that this could be a story or an attempt at informing/history. It’s likely part of a book of some kind, though I’m curious as to what kind.

I’m also curious if this could also be some depiction of heaven or enlightenment or some other space you could reach with time and work? Is this a place you can go or that exists/once existed? A utopia– imaginary or real? The focal point character is sitting in padmasana, as I referred to earlier, which also makes me think this could be more religious. There’s so much color and energy around him specifically; could he be a kind of leader other than a king, but I imagine he’s both a spiritual and actual ruler.

The yellow (gold?) in the sky makes this feel like a sunrise which definitely adds to that sensation of this being a beginning/dawn of the world, civilization, or just… something new. I’m not sure what. I love the detail in the greenery as well, and I’d love to take a closer look at that top left corner.

Kaaba ; pre-Islamic monument, rededicated 631-32 CE ; Mecca, Saudi Arabia ; 15 x 10.5 x 10.5 m ; Granite masonry, gold, covered with silk curtain and calligraphy in gold and silver-wrapped thread

This is the Kaaba— the holiest shrine that exists in Islam, and the destination of Islamic pilgrimage (the hajj) for all who are able in their lifetime. In Islam, five-times daily prayer is done in the direction of Mecca and the Kaaba rather than Jerusalem, and the direction of these is marked in all mosques. When people do visit the Kaaba, they circle it seven times and often kiss the Black Stone or al-Hajar al-Aswad on the eastern corner of it (believed to have been given to Ibrahim by the angel Gabriel).

Muslims believe that the Kaaba was constructed by Ibrahim and his son Ismail, and that when Muhammad returned to Mecca after being driven out to Medina, the Kaaba became a central space in worship (and thus pilgrimage).

This is just some of the story of the Kaaba, but it’s undergone many renovations and changes and looks little like what it once was! Now, it’s an incredibly unique religious structure. Its solid gold door is absolutely gorgeous and incredibly detailed, and a large black cloth covers the rest of it as a way to show respect and reverence to the site (which makes sense, with how much covering and modesty is emphasized in Islam). My guess is that the door and embellishments around it are covered in calligraphy of Quranic verses, but I couldn’t be sure. I also don’t remember if it’s legitimately restricted entry (outside of being restricted to Muslims) for any reason other than preservation of the Kaaba, and I’m curious to know more!

I’m also curious about the color symbolism. Was a black chosen for practical reasons like its ability to hold up, or is it more symbolic? Maybe exploring evil or just potential and the unknown. Most people who visit wear white which seems like it supports that idea. Also, if I remember correctly, people believe that al-Hajar al-Aswad is now black because it has absorbed the sins of the people who touched it and was once white, which again makes me think that this blackness represents both unattainable things and sin. The gold could also represent the sun, god, wealth, divinity, and so much more. It being a cube is interesting to me; it wasn’t always one, but why was it designed that way later on? Is it something about balance?

Veranda Post of Enthroned King and Senior Wife ; 1910-1914 CE ; Ikere, Nigeria ; 152.5 × 31.8 × 40.6 cm ; Wood and pigment

This piece, to me, is reminiscent of a family portrait. It’s made of wood, which is interesting, because it was important enough to create but not important enough to be made in stone to last forever. The fact that the person in front is sitting on a huge chair (throne, I imagine) with servants at his feet (small due to the choice to use hierarchical scale) makes me think he’s a king. One of the servants seems to be playing a musical instrument which intrigues me! The king’s feet are also kept from touching the floor which, if I remember correctly, is often a custom for rulers throughout the world. The crown is definitely really elaborate which interests me; I’m curious about the symbolism within it. There seems to be a bird atop it, maybe symbolizing transformation and ingenuity?

The woman behind him, I imagine, is his wife (or perhaps the most important one). It’s interesting to me that she’s depicted standing and seemingly much taller than he is. Would that not make him lesser? Is it to make her seem like a powerful nurturing figure? She’s blue, so is it like in Egyptian art, where she’s meant to be a goddess or a spirit of some sort? Or just supernatural in some way? Are women just viewed as more important in this society? She has very emphasized breasts which definitely leans into the idea of fertility and motherhood to me. She’s wearing a very elaborate headdress and wearing beaded bracelets (coral?) that match her husbands’. She’s also connected to him through her hands on the back of his throne. I wonder why she’s baring her teeth. I know it’s hard to keep them clean & healthy, so maybe it’s a symbol of wealth or status?

Bundu Mask ; 19th-20th century ; Moyamba region, Sierra Leone ; 47.9 x 22.2 x 23.5cm ; Wood, metal

I’m really intrigued by this piece although I don’t know exactly what’s going on with it. It’s obviously a bust of a person, and their facial features are very small— almost like a baby’s or an old man’s. The figure has this very large helmet on and the artist used some sort of hair from the bottom of the helmet as if to create a sort of poncho/shawl. It honestly looks very nice, though, which gives me the sense that the person they’re portraying has power and wealth (a sense I also get because they have a bust of them). The sort of vague waviness of it makes me think also, though, that it isn’t quite human— more like a spirit. The helmet or headdress reminds me of the dress of a general/decorated officer. It could also simply be hair with a smaller headdress (or simply an abstract representation of hair) and even necklaces or just neck fat, in which case I don’t imagine it’s a general, but still someone or something powerful. Even the idea of it as a helmet feels ceremonial, though— it’s not like a general wears this all the time.

I’m curious as to what the small face represents— or it could be more that the head is big (thus representing great intelligence?). The sort of squinted face also does give me a sort of wide and dedicated energy, likely because of its aged look. It also feels like there’s a sort of smirk in there because of the smile lines, which I’m curious about. Again, I just keep coming back to ‘why that expression?’ It’s interesting that the features are so small and fragile, though— is this meant to be a woman? In general, the piece’s strong ambiguity makes it seem to me like it’s most likely a spirit of some kind.

Wall Plaque from Oba’s Palace ; 1550-1680 CE ; Benin, Nigeria ; 49.5 x 41.9 x 11.4 cm ; Brass

This piece is incredibly striking! It seems to be depicting some sort of king or ruler and his attendants using brass— the king being the largest figure in the center with lots of jewelry and riding sidesaddle on a horse. There’s a lot of symmetry in the piece, so it’s interesting that he’s riding sidesaddle. Is it ceremonial? Also, that his jewelry is covering his mouth is interesting; it’s reminiscent of the ‘speak no evil’ sort of imagery. The others in the image scale in size likely based on importance within his court (two really small ones near the top and at his feet, slightly larger but child-sized ones beside him, and two almost as large as him shading/shielding him). Their heads are huge, which is interesting; is it trying to emphasize their intelligence? I’m also curious if the two shielding him are doing so from battle or the sun. They all have these very serious and intense faces, like they’re doing something important. I wonder if it’s meant to be a specific event or representative of the leader’s rule, maybe?

There are some interesting floral motifs behind them that I’m curious to know more about. Each is only four petals— maybe bearing resemblance to the cross? Is this post-trade/colonization work? Come to think of it, it’s likely that the horse was traded as well and he learned sidesaddle as a result of trade, so I wouldn’t be surprised if Western influence had made a huge impact on African art already by this time. That said, the flower could also be trying to express a flourishing kingdom/army and emphasizing his growth and power as a leader.

I’m intrigued by the differences in their regalia. I know it’s meant to differentiate status, but I want to know the specifics! I also wonder what the point of this piece is. Is it meant to tell a story? Be a display of power? Commemorate leaders? If so, were there more of these plaques? This one is pretty high relief and seems intended to hang up like a tapestry.

Bandolier bag ; 1880s CE ; Wisconsin, United States ; 87.6 x 30.5 cm ; Wool and cotton trade cloth, wool yarn, glass, metal

This bag is truly mesmerizing. There’s an immediate sense of movement in the beadwork, like the designs are shifting just beneath the surface. The symmetry is striking, but it isn’t rigid— it feels organic, like the shapes are growing into each other rather than just being mirrored. There’s something about the patterns that reminds me of botanical imagery like flowers/plants and even butterfly wings, in parts, and there’s also a softness in the color choices. I’ve just noticed, actually, the face in the center! There seem to be arrows pointing in toward the sides of the head, so it could be focusing on listening and storytelling in some way. I’m not sure, though. The beaded tassels at the bottom especially add a kind of fluidity, like a fringe swaying as someone moves.

I definitely wonder about its owner. The piece is obviously Native American— a guess says maybe Ojibwe? I can imagine someone wearing it across their chest, the bag resting at their hip. I’m curious if it’s meant to be everyday or more official? Is it used in any specific job? Beadwork is intricate and beautiful, but I also think it’s easy to forget that it’s somewhat everyday, too, just because it doesn’t seem everyday to our own tastes. At the same time, beadwork always feels really powerful to me— like a form of storytelling, even if I don’t have the language to fully understand it. I feel like the choices— certain blues, pinks, browns, the way the motifs interlock— mean something specific, that there’s intention behind it beyond just “this looks nice.” The contrast between the bright, angular bands of pattern along the strap and the slightly softer, more intricate design on the bag itself makes it feel dynamic, like it was designed to be seen in motion.

And looking at it makes me want to touch it— imagine the cool smoothness of the beads, the tightness of the weave, the slightly rough edges of the tassels. It’s fascinating how beadwork does this, how something so small-scale, piece by piece, can create a textile that’s both durable and delicate, solid yet shimmering.

Thunderbird Transformation Mask ; ~19th century ; somewhere near Alert Bay, Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada ; 78.7 x 114.3 x 119.4 cm open, 52.1 x 43.2 x 74.9 cm closed ; Cedar, pigment, nails, leather, metal plate

I’m really captured by this piece. The colors are so beautiful and every line feels precise and intentional. It almost feels alive, like it’s watching you just as much as you’re looking at it. It’s not just an object, but something more— like maybe a story, a ritual, a performance frozen in two frames.

I love how the reds, blacks, yellows, and blues pop against each other, almost vibrating, while the symmetry of the design feels like it’s holding chaos at bay. The fact that the face moves— opening and transforming— gives me the sensation that two worlds are colliding, with inner and outer faces telling completely different stories. It really does feel like it's meant to tell a story— maybe through ritual or dance? Its opening up reveals this new perception as if some new aspect to the story has happened. I feel like it could be showing a supernatural experience— like an encounter with a god that at first presented as an animal. I also wonder if it’s meant to tell new stories or retell old ones— an aid for myths to be passed down. If it is for ritual, I imagine the second.

I’m curious as to what’s going on inside the mask, though. I don’t really get it. It seems like a man has these two snakes/creatures coming out of either side of his head. This could be a depiction of a god, or maybe it’s meant to tell some other story I’m just not aware of. Are the creatures behind him, closing in? Aiding him?

Calendar Stone aka Sun Stone ; 1502-1520 CE ; Mexico City, Mexico ; 12 ft diameter x 39 in thick ; Basalt

I know this piece; it’s one of the most famous Mexica pieces I can think of! It’s massive, which this photo doesn’t show, but is very impressive, and its size gives it a sort of undeniable energy— as if it was made to be seen, to demand attention. Looking at it feels almost like I’m being pulled into the past, but not gently. It’s loud, with all its intricacy. Every inch of the stone is carved with something deliberate— figures, patterns, symbols— and that density feels like it’s meant to remind you of how much this object holds. History, time, and cosmology are all there, if layered and heavy.

The central face, which I think could be Tonatiuh (sun god, given that it’s literally the center of the sun), stares out with this sharp, almost demanding expression. Its tongue is shaped like a blade and feels a bit aggressive, but I imagine that’s the point. I’m not sure of what all the symbols that surround it mean, but I can infer. Obviously there’s the central face (who’s holding something in a tight grip in each hand), and then there’s other ‘gods’ or at least figures of some kind right around the sun face. From there, you can see some smaller figures of animals that could represent the rest of the world. But it also feels like it’s not trying to portray everything statically— it’s a circle, cyclical, and feels like it’s exploring those cycles of man & empire. Violence, war, love, nature, relationships in general. Something like that. It’s also clearly directional, with its little spikes! It’s trying to give a history— a calendar and a catalogue in one. That makes me wonder if it could be state-sponsored?

I can’t stop thinking about the way the circles radiate outward, too, like ripples in water. Each ring seems to have a layer of knowledge— about the universe, their gods, the sort of order of the universe. The glyphs and figures carved into those rings are so precise, so carefully done; it’s as if every piece has its own story.

I feel that aside from being a calendar, this could be a tool of ritual. It’s already pretty clearly a way to mark time and history, but also a reminder of sacrifice, of the balance between gods and humans, of the literal lifeblood that kept the world moving. You can almost feel the weight of that belief system, how deeply interconnected everything is.

Moctezuma’s headdress ; Made before 1596 CE ; Unknown City, Mexico ; 46 in height x 69 in diameter ; Gold, Feathers of Quetzal, Lovely cotinga, Roseate spoonbill, Piaya cayana

This headdress immediately draws the eye in with its radiating pattern of vibrant green feathers, edged in blue and anchored by reds and golds at the base. It looks very regal— a piece crafted with immense care and meant to be worn by someone powerful and significant. I’m curious if it’s more of the level of a king or a God— maybe someone who’s both? I say that because the symmetry of the design, paired with the richness of its materials (feathers, gold/jewels), gives me the impression that this wasn’t made just to impress but to actually elevate the wearer to another level. It also seems to be an Aztec piece just based on design and aesthetics.

The feathers are very long, soft, and carefully layered, and they seem to be quetzal feathers. They add to the feeling of rarity and divinity since quetzal birds were sacred in many Mesoamerican cultures. This specific piece could be a reference to Quetzalcoatl. Either way, it’s not just decorative; it’s symbolic. The green of the feathers could represent fertility or life, while the gold at the base ties it back to power, wealth, and the sun. The reds might evoke blood, sacrifice, childbirth and thus life, or the earth. The turquoise was likely associated with both fire and young warriors and rulers because of the god Xiuhtecuhtli. The whole piece comes together like a story— and very much one of power.

I already said I’m not sure if it’s meant to be worn by a ruler or God, or maybe even someone representing a deity during a ceremony. Regardless, though, it feels larger than life, like its purpose was to bridge the wearer and the divine. There’s a weight to that idea— that this headdress might have been central to something spiritual or ritualistic, not just a marker of power but a tool for connecting to something greater.

It feels overwhelming to look at, not in size but in the amount of detail and meaning packed into one object. There’s a sense of reverence in how it must have been made, as though each feather and bead was chosen with intent. And even now, removed from its original context, it still carries that energy; it feels like it’s watching us as much as we’re watching it.

Coyolxauhqui Stone ; 1473 CE ; Tenochtitlan aka Mexico City, Mexico ; 10.5 ft diameter ; Volcanic stone

I feel like I have a bit of an unfair advantage with this piece, having more knowledge than most about Mexica/Aztec culture and myth. This seems to be depicting Coyolxauhqui (Bells Ringing On Her Cheeks) having been dismembered and decapitated by her brother Huitzilopochtli (who was birthed by his mother for the sole purpose of fighting those of his siblings who wanted to kill her) because of her plot to kill their mother, Coatlicue. She’s fairly naked, which I imagine would be viewed as shameful, which is also interesting because her initial reason for killing her mother was shame and disgust around her mother’s own pregnancy and sexual activity.

I could see this disc being a monument of some kind, as it’s very high relief and technical and recounting this myth could serve as some sort of lesson. I wonder if it’s a warning, though– whether to the people of the Mexica empire, the people of conquered city states, or even just flat out enemies. It’s clearly recounting an intense story about betrayal and the consequences, and I could imagine it working well to try and warn/repel others from rebelling or starting anything, really.

The piece itself is really beautiful. Coyolxauhqui is looking upward– maybe in repentance or hope that something might save her– but she also seems to have accepted this fate. She has a snake belt around her waist, with a skull tied to it on one side, a beautiful headdress, and bells on her cheeks– all classic symbols to identify the figure as her– but I’m not sure if there’s anything more that these symbols are meant to mean about her (except her snake belt, which I think she got from her mother). I think it’s interesting that she also keeps her snake belt despite the clear attempt to humiliate her– she keeps this aspect of her mother but also her nobility. I do know she’s the goddess of the moon and milky way, but the rest of her symbols don’t seem explicitly related to that.

Great Serpent Mound ; 1070 CE ; Ohio, United States ; 1300 ft. length ; Earth

This is a truly huge monument! I’m really drawn in by its serpent-like form, and also curious how it was made. Honestly, all landscaping that changes the land itself is kind of beyond me. It weirds me out in a cool way.

I love that this sort of needs a far-away eye to really see what’s going on. Walking alongside it would make it harder to get the full picture of the monument. This makes me feel like it’s likely not art for the sake of art, but maybe something more important. I know serpents are pretty important in a lot of Indigenous cultures and thought to have some sort of supernatural, magical, or even just medicinal powers, so the choice of the serpent could be to signify health and magic for the land, maybe? Or maybe it was meant to be used as a site for rituals? It could also be a path to walk for reflection or something like that… I’m not sure!

The fact that it’s a crescent is really cool to me, too, and makes me consider ties to the moon, planets, and space in general. Could this be related to seasonal celebrations or beliefs?

I honestly don’t have a lot to say on this one, but it’s really beautiful to me. It makes me feel small, and I’d love to see it in person. Truly an interesting monument!

Spiral Jetty ; 1970 CE ; Rozel Point, Box Elder County, United States of America ; 15 ft × 1500 ft ; Land art sculpture with salt crystals, basalt rocks, and mud

I know this piece and love it deeply! This is a land sculpture that exists in Salt Lake City, Utah, and is made (if I remember correctly) primarily of basalt stone and soil. I’m a huge fan of artists who interact with nature directly in their work, and this piece is no exception!

The piece definitely seems to be commenting– to an extent, at least– on humans intervening in natural spaces and how that affects said spaces depending on how intentionally we move through them. How can we do things that leave less impact? Is less impact the goal?

The artist decided to create a spiral formation– a symbol that often represents rebirth, growth, progress, time, evolution, etc, and also aligns with concepts of mother nature and the sun in many cultures– feeding back into this theme of interaction with nature and the slow progression & change that occurs in nature with time. Spirals are also prevalent in nature a lot, too (golden ratio!), so it makes sense they’re associated with mother earth. It also makes me think about how we’re speeding up those changes the more we interact with the earth in a selfish and greedy way (climate change… yay…). I wonder if selfish is even the right word– is it selfish to do something that will eventually hurt us, or is it just self destruction? I guess that depends on whether you view yourself as part of humanity or a whole separate being.